From the horse’s mouth

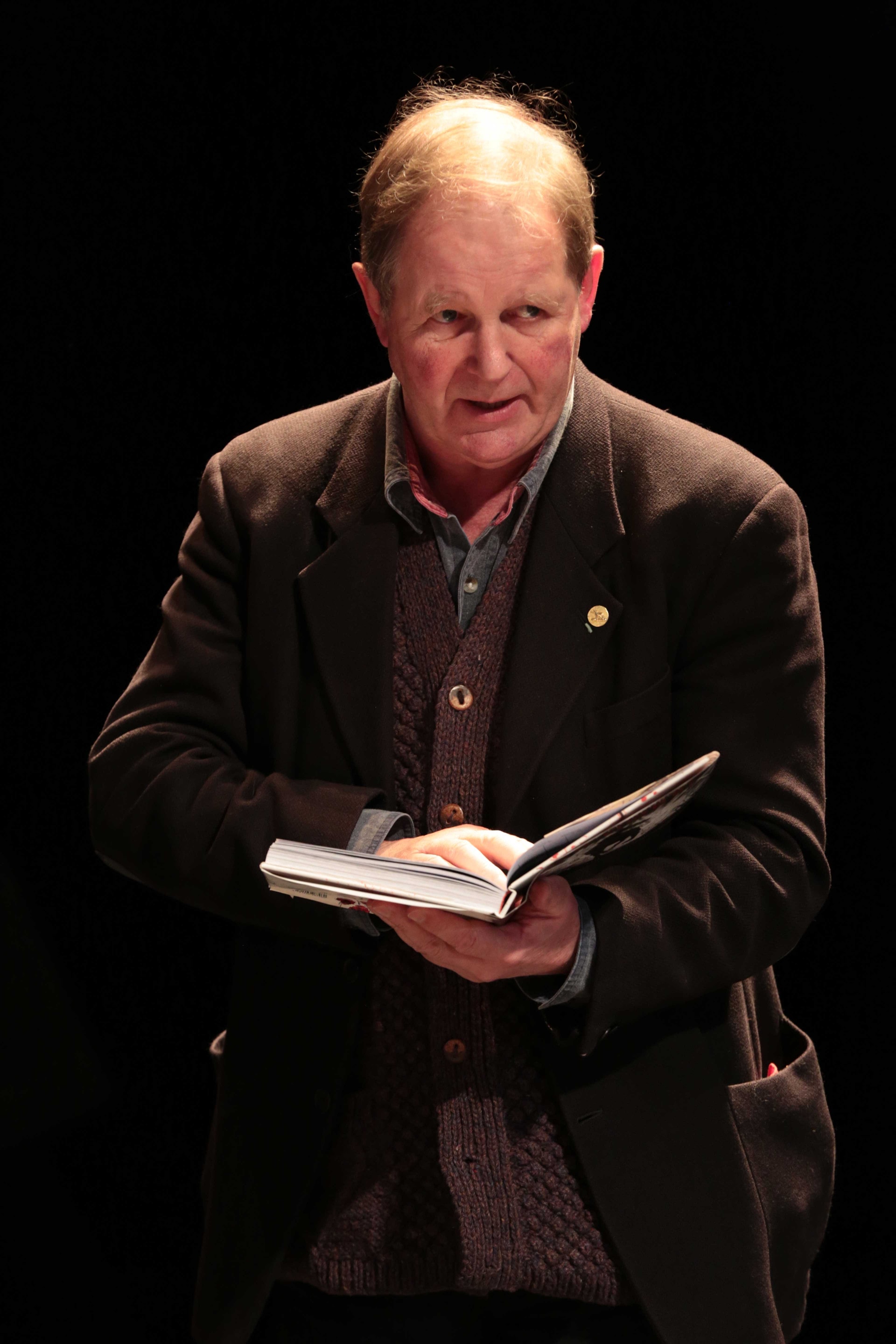

Tue 2 May 2017It’s easy to imagine Michael Morpurgo as the teacher he once was. Twinkly-eyed, kind and interested in his pupils, but with just enough steel that discipline wouldn’t be a problem in his classrooms either.

He must have been a favourite at the small school in Wickhambreaux, just outside Canterbury, where he first became a storyteller: “There was a time that came, and all teachers know this, at the end of the day when you’re really tired and the children are tired, and you’re wondering how you’re going to get to half-past three.”

Head teacher Mrs Skiffington suggested Michael read a story to the children from 3pm, something he believes every school in the country should do: “If I chose the book right, they listened. And one day I ran out of stories that I really loved, is the truth of it. I started one with these kids that I knew was wobbly, and I could see the look on their faces, they were picking their nosed, looking out of the window, and I could see it wasn’t working.”

With 14 more chapters of this ‘stupid book’ to read, Michael asked the advice of his wife, Clare, also a teacher: “She said ‘Well, don’t bore them again. Make up a story. You’re quite good at telling lies, make something up.’ So I did that, and it worked.”

It was this story which led to his career as a writer: “I realised they [the children] were listening, and they liked it, and oh boy, did I like that, because that’s power. So I realised,’you can do this stuff’, and I went on the next day. And it went on all week, and at the end of the week, Mrs Skiffington, came in and sat at the back, because she’d heard about Mr Morpurgo’s stories.

“She came up afterwards, and said ‘Michael, that was wonderful. Here’s what I want you to do for me, I want you to write it out over the weekend and give it to me on Monday morning.’

“No one had talked to me like that since I was about five or six, but I did it. She had a cousin or something who worked at Macmillan, and she sent the story to them and they wrote me a letter, which I’ve still got. ‘Dear Mr Morpingo, [he rolls his eyes at the publishers’ mis-spelling of his name] we’ve just read your story, could you write five more, and we’ll pay you £75.’ Eat your heart out, Roald Dahl.”

When Michael chose to leave teaching, it wasn’t to be a full-time writer, but to start the charity Farms For City Children, which he and Clare still run. It was one of the children who visited the charity’s farm in Devon, who provided him with the impetus to write War Horse.

The idea for the story had come from a conversation with a First World War veteran in Michael’s local pub (The Duke of York in Iddesleigh, Devon), along with the idea that a horse would be the perfect vehicle to tell the take with neutrality, not taking one side or another.

What held him back, he says, was the worry that a story told by a horse would be too sentimental. What convinced him otherwise was coming across a young boy on a visit to the charity, who was usually almost mute, talking non-stop to one of the farm’s horses: “And the horse was listening, and it understood that this was important. I knew it didn’t understand what he was saying, that would be stupid, but it understood that this was important.”

War Horse was published in 1982, and initially saw only modest sales – it wasn’t until the National Theatre adapted it as a play, complete with the famous puppet horses, that its popularity soared.

It’s clear that Michael has a huge affection for both the play and the people who perform in it: “I go on stage from time to time. I put on a costume and I become part of the crowd. You wouldn’t recognise me and no one does, I’m part of a crowd at the auction scene, and I sing a couple of songs. I love to feel part of it.

“I’m very conscious of the fact that night after night after night, these guys, 60 of them, go out there and they work their socks off, every single night, and matinees as well, and they’re exhausted.

“You should hug the puppeteers – there is nothing there to hug except muscle and bone! They work so, so hard, and I’m conscious every night that I’m sitting there having my cup of tea or whiskey or something and they’re out there working their socks off. So I make a pilgrimage, go and act it with them. I wait until I’m asked, I don’t force myself on them… I don’t force it. What I say is, I’m ready to come when you want me, and then I get a phone call ‘you can come now Michael’ “.

It’s not surprising that Michael relishes the chance to appear on stage – as the child of two actors, acting is clearly in his blood. Not only that, but Michael’s parents fell in love while working at the old Marlowe Theatre on St Margaret’s Street: “They met at RADA, but they fell in love at The Marlowe Theatre, in 1936. I’ve got a photograph of them standing outside the theatre, with a whole troupe. In those days they did rep, so they did about three different plays a week.”

Michael has promised us that he will be visiting the current Marlowe Theatre during the run of War Horse: “The ghosts of my mum and dad wouldn’t forgive me if I didn’t.”

War Horse: Friday 15 September to Saturday 14 October 2017.